Bio-art beyond the edge of everything. By Anne Farren and Andrew Hutchison

Introduction

Bio-art is an artform that sits beyond the edge of everything that is familiar and comfortable… The exploration into the application of bio-technology, in particular the use of cell cultures as an art form, is new and controversial.  | | TC&A : Worrydolls |

Perth, Western Australia is home to some of the most challenging work being ‘created’ within the realms of bio–art. This is a paradox for many looking on and maybe even for those involved. , Perth (geographically) and bio-art (intellectually) sit at the very edge of the known. Folklore tells us that the phrase “Here be Dragons!” was put on medieval maps when early cartographers came to the edges of the known world (in truth it is apparently only written on one map, and in Latin1). For those in the Middle Ages the notion of Dragons perfectly embodied the mythological, wondrous and strange possibilities that existed on the edge of the known. Today artists are drawn from the four corners of the globe to seek out the mythology, wonders and strange possibilities presented by one of the most isolated cities in the world. And as Professor Julius Sumner Miller would have asked, “Why is it so?”

In a modern world, mapped by satellites, where we know there are no actual dragons, but where we see bizarre animals every night on TV, Australia holds this mythological position in popular Northern Hemisphere thinking. Australia is thought to be so far away that you cannot get any further away. It is upside down, it has animals and plants that defy the very laws of nature, it is huge and empty; dry but oceanic; simultaneously ancient and one of the newest nations on Earth. It represents the very edge of the known and familiar, a paradox of logic.

However, Australia is also the highest taxed, most multicultural, most immigrant, most urbanised society on Earth, with four of its cities ranked in the top ten most liveable in the world (the United States has none)2. Australians, along with their near cousins the New Zealanders, are also reputed to be the most travelled people in the world, possibly because of their ridiculous distance from everywhere else. All this, that appears paradoxical to others, appears perfectly normal to Australians.

So if you are an Australian, and you need to think of somewhere far away, strange and unknown, where do you think of? Where does Australian popular culture write “Here Be Dragons!”? It writes it next to the most remote city in the world, Perth, a relatively small city on the West coast. In Australian TV soap operas, if a character needs to be written out of the story line without actually killing them off, they move to Perth. This serves to ensure that they will never come back, phone or write.

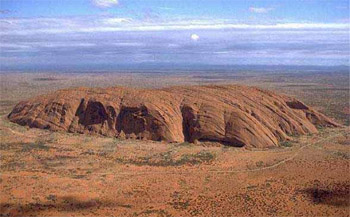

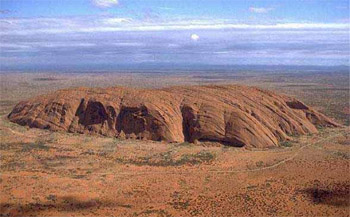

Perth’s special place in Australian perception takes some explaining. Australia’s population of only twenty million primarily hugs the coast of an island continent as large as Europe, or the continental United States. Fifteen million or so of those live on the Eastern Seaboard, - the Pacific coast. This gives Australia its status as a Pacific nation. Perth, a city of two million, lies on the other side of the continent. The separation between east and west is similar to the distance between New York and Los Angeles or, for Europeans, the distance between Madrid and Moscow. But what is very, very difficult is to get people from outside Australia to understand is, that apart from Uluru (one of the largest single rock formations in the world) and Alice Springs, there is very little between Perth and the Eastern seaboard except unpopulated, semi-desert. If Australia is the edge of the unknown, then Western Australia, and Perth, are off the edge altogether.

Perth is the only settlement of any notable size in a space so vast that it is almost beyond credible description. Western Australia is a single administrative jurisdiction that stretches for three days driving at high speed from West to East. From North to South, Western Australia extends literally from the equatorial tropics all the way to the cold Southern ocean. Perth is so far removed from the typical Australia that it isn’t even in the Pacific. It is on the eastern edge of the Indian Ocean. If you face westwards, out to sea, the next stop is Africa. As previously stated Australia has four cities in the top most liveable cites in the world, and Perth is one of these four. It produces international movie stars, Nobel Prize winners, breakthrough medical technologies, mass murderers and corrupt politicians just like every other world class city.

So how does this extreme isolation create a unique perspective on the world. And why has Perth become a world focus of bio-art? Is it a set of improbable circumstances, or is something special happening on the edge of the edge?

Salt Lake – at the edge of the edge ‘05

© Photo: Ashley De Prazer

At the edge of the edge

Perth is a relatively small community which clings to the narrow coastal plain on the edge of the continent. The people living in this marginal environment are driven by its challenges and inspired by the achievement of others. The reality is that it is a land at the edge of the edge which has cultivated innovative and ground breaking bio-medical research. Work such as that of Dr Fiona Wood and C3 (Clinical Cell Culture) into the development of the ‘spray on skin’, used most notably to treat the Bali bomb victims in September 2002. And Nobel Prize winners, Professor Barry Marshall and Dr Robin Warren who worked in the early 1980s on gastro-associated dyspepsia and ulcers which revolutionised the treatment of duodenal ulcers by enabling an antibiotic cure and resulting in significant reductions in the prevalence of gastric cancer.

It is a community which has initiated international conferences and projects such as the space between Conference ‘04 and the ongoing initiative BEAP (Biennale of Electronic Arts Perth). Both of these conference/festivals were hosted by Curtin University of Technology and featured some of the most innovative work dealing with the relationship between new technologies and the arts.

TC&A: Victimless Leather 2004 TC&A: Victimless Leather 2004

the space between Conference Exhibition, John Curtin Gallery.BEAP (http://beap.org/site/index1.html) has an ongoing commitment to bio-art and has played an important part in the development of the international profile of Perth’s bio-art activity. The inaugural Biennale was held in 2002, and showcased leading practitioners in electronic arts from around the world. The thematic focus for BEAP02 was LOCUS - "Where we believe consciousness exists".3 As part of the 2002 program BEAP partnered with Symbiotica in the promotion of BioFeel (http://www.fishandchips.uwa.edu.au/exhibitions/biofeel.html ), an exhibition curated by Oran Catts and held at Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts.

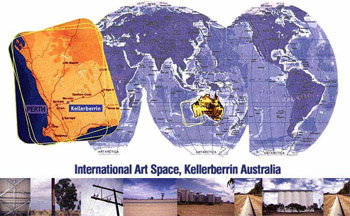

It is a community and culture which has nurtured the establishment of PIAF (Perth International Arts Festival) and organisations such as AGWA (Art Gallery of WA), PICA (Perth Institute of Contemporary Art) which all have, for more than twenty years, been instrumental in providing opportunities for the development and presentation of innovative and experimental art forms. More recently, we have seen the emergence of IASKA (International Art Space Kellerberrin Australia) an international art space which sits in the marginal Western Australian wheat belt, at the edge of the Western Desert.

While all of these organisations provide a rich and supportive environment for the arts in WA, PICA played an important role in the development of bio-art in Western Australia, through the provision of funding for early Tissue Culture and Arts (TC&A) projects and exhibitions. Most significant to bio-art in WA has been the establishment of SymbioticA which was founded with the specific view to supporting investigations into the relationship between bio-technology and art. It is an organisation which is now leading the world in the practice of bio-art.

While all of these organisations provide a rich and supportive environment for the arts in WA, PICA played an important role in the development of bio-art in Western Australia, through the provision of funding for early Tissue Culture and Arts (TC&A) projects and exhibitions. Most significant to bio-art in WA has been the establishment of SymbioticA which was founded with the specific view to supporting investigations into the relationship between bio-technology and art. It is an organisation which is now leading the world in the practice of bio-art.

http://www.iaska.com.au/ © IASKA

These organisations support a diverse range of arts practice and provide opportunities for international artists to experience this unique environment. Western Australia has a huge diversity of ecosystems, but the one which is predominant around Perth is what North Americans would describe as ‘prairie’ – almost completely flat, with small trees clinging precariously to the few creek beds, and the enormous visually crushing weight of the empty blue sky. This country is host to the “wheatbelt”, and it is interesting to speculate how this astonishing singularity of physical environment affects our perceptions. IASKA sits at the edge of this marginal landscape, a two and a half hour drive from the closest large town or city, Perth. International artists visiting this space are challenged and often confronted by the strange landscape, its sense of space and isolation, which is so familiar even to those living in the city.

Wheat Field

http://www.iaska.com.au/images/iaska/isaka/field.jpg © IASKA

Awareness is heightened by the tenuous nature of our existence in the fragile and somewhat surreal environment. But it is this very ‘environment’ which is also host to one of the most innovative initiatives in the scientific/art world, SymbioticA.

SymbioticA - History & Landscape

The vision for founding SymbioticA (www.symbiotica.uwa.edu.au) in 2000, was the result of a unique collaboration between Oron Catts (artist, and part of Tissue Culture & Art www.tca.uwa.edu.edu ), Stuart Bunt (neuroscientist/artist www.iaaf.uwa.edu.au/smbunt/ ) and Miranda Grounds (cell and molecular biologist www.school.anhb.uwa.edu.au/PersonalPages/Grounds/). While it may appear to be a paradox that Perth has emerged on the global map as a key centre for bio-art, the environment in which bio-art in general and SymbioticA more specially have grown is in some respects quite fertile.

Initiatives such as the founding of the WA Skin Culture Unit at Princess Margaret Hospital for Children in 1993 forged new ground in cell culture technology. With the founding of the WA Skin Culture Unit evidence of a tissue culture, culture appears to have emerged. As the twentieth century drew to a close and most of us focused on the concerns of the potential millennium bug the establishment of the McComb Foundation further advanced the potential for research and development of innovative skin culture technologies. Later in the same year, Clinical Cell Culture (C3) was founded with the aim to commercialise technology developed by the McComb Foundation.

SymbioticA emerged in 2000 from a context of long standing relationship between the arts and sciences which existed at the University of Western Australia. Since 1967, Western Australian artist Hans Arkeveld has been artist in residence in the School of Anatomy and Human Biology (ANHB). His presence and long term relationship within ANHB paved the way for the development of new collaborations between the arts and sciences and the establishment of Perth as a focal point for bio-art internationally. Of particular importance was the development of a bio-art culture in Perth was the relationship between UWA and Tissue Culture & Art. TC&A is the artists partnership of Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr which was formulated in 1996 and included Guy Ben-Ary for the period 1999-2003.

Oron Catts became interested in the potential of this new area of bio-art through his Honours studies in Design at Curtin University into the potential relationship between design and bio-technolgy and Ionat Zurr came to the partnership from a background in photography and media studies. Professor Miranda Grounds facilitated the connections between TC&A and UWA , enabling the commencement of their research into tissue culture, at the Lions Eye Institute. TC&A’s work at the Lion’s Eye Institute resulted in the development of the first bio-art exhibition, TC&A Project 1, which was held at PICA in 1998. In the same year the Lawrence Wilson Gallery at UWA also hosted an exhibition, Art and Science, further welding the relationship between the arts and sciences. There was fertile ground for the establishment of SymbioticA.

According to Stuart Bunt, the Scientific Director of SymbioticA, the creation of this forum “raised new issues of language and ethics at the boundary between the living and the dead and the artistic and the scientific. Our aim is to provide both a “safe harbour” and a resource so that artists can penetrate the hallowed temples of the scientist on a more equal footing.”4 Visiting the ‘lab’ based in the ANHB building at UWA, you experience tangible evidence of this. Artists work in an environment filled with images, equipment and materials referencing sources, ideas and influences from both the arts and sciences seamlessly merged and are surrounded by fascinating and macabre organisms both living? and dead? Resourcefulness The Western Australian physical and cultural environment has bred a nature of resourcefulness. As an isolated colony we were left to our own devices for survival. In the absence of quick and easy access to many resources because of the tyranny of distance, an attitude of making do and problem solving has emerged as a part of our cultural tradition. From this history has emerged a nature of freedom and non-conformity which encourages resourcefulness and open-mindedness.

This attitude is manifest in those involved in the founding of SymbioticA. It is demonstrated in the story behind the construction of the facilities necessary to create the ‘lab’, which was needed to create a focal point and home for this great idea. “At this time CTEC [Clinical Training and Education centre is based at The University of Western Australia – Perth. (http://www.ctec.uwa.edu.au/) ] was being built on the side of Anatomy and Human Biology. With the architects help, while all the cranes etc. were still on site, we were able to build the SymbioticA "lab" on top of the ANHB building by raising the roof.”6

SymbioticA “lab”

Photo: SymbioticA

What has been created is a cosy, intimate attic that accommodates artists, residencies, forums and exchange and with direct access to UWA based facilities such as CTEC.

Within this scientific context SymbioticA has been able to create and recognise a significant role for the artist. The artists working at SymbioticA have hosted a diverse range of projects, from ‘Pigs Wings” (TC&A ) to fragile fungi dresses (Donna Franklin 2004) .

TC&A: Pigs Wings

Donna Franklin : Fibre Reactive, 2004

Photo: Robert Frith image courtesy of SymbioticA

The projects conducted at SymbioticA are constantly challenging the boundaries of acceptance and understanding for the scientist, artists and community, taking us all into the fearful and fantastic lands of the ‘dragon’. Of particular significance has been the MEART project ( http://www.fishandchips.uwa.edu.au/ ) initiated in 2001 and which still continues to stimulate debate about creativity and consciousness. As the first work to receive international attention, through Ars Electonica, it is described as a flagship project for the SymbioticA Research Group and is probably the best example of a collaboration in which artists and scientists worked so closely together . “The installation featured a laboratory/studio set-up, prototypes and documentation of the project, and was an example of the research being conducted in SymbioticA – The Art & Science Collaborative Laboratory, School of Anatomy & Human Biology, University of Western Australia . It was the first generation of the project.”7 MEART is a project which continues to represent the potential that has been created by the unique collaboration between art and science that is SymbioticA.

”Meart – The semi living Artist”, by SymbioticA Research group in collaboration with the Potter Lab.

Credit; SARG & the Potter Lab

Meart – The semi living Artist”, by SymbioticA Research group in collaboration with the Potter Lab.

The robotic Arm, Australian Culture Now, 2004

Photograph by Phil Gamblen

Comments on bio-art

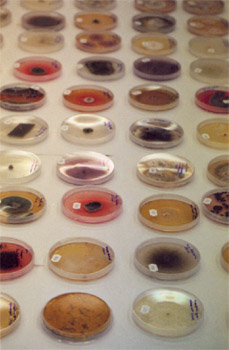

While it would seem that the focus of a centre such as the SymbioticA ‘lab’ is primarily about access to the latest in bio-technology, this is not the case. it is important to keep in mind the comment made by Ionat Zurr, that “bio-art is more about life and not just new technology. Low technology has its place. For example the work of Donna Franklin”.8 Donna works with fungi, a material that has traditionally been used to dye cloth for centuries and one which is firmly ensconced within the language of textiles. However instead of extracting the colour, she cultivates the organism to create ‘living’ colour and texture.

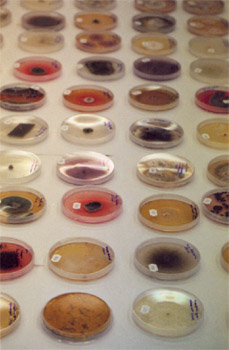

Fungi Cultures. 2003 Various specimens. Fungi Cultures. 2003 Various specimens.

© Donna Franklin Oron Catts, says “that they (TC&A) are more interested in the problem and artistic discovery, than new technology.”9

SymbioticA artist Guy Ben-Ary comments, “I think that one of the roles of artists is to deal or comment about what is happening in our society. Especially artists that are working with or developing [new] technology. We are surrounded by technology and we are sucked into it on a daily basis in our capitalist society without even being part of this process. Now when it comes to Biotech it is even more dangerous and the tools of modern biology are changing our bodies and perceptions of what is alive and what is not. Artists should engage in biological related technologies as a medium of suggestion for alternative and contestable futures and even more importantly – to inform and try to generate a public dialogue regarding the possibilities of these technologies. The artists should adopt a visionary model by preparing society for the greater challenges ahead in the fields of biotechnology.”10 Stuart Bunt comments that “ biotechnology is moving from a phase of discovery to a phase of application and creativity - this is seen by many as threatening. Many have a different attitude to a mechanical invention (who cares about the "threat" of computers any more?) than a biological invention such as genetically modified organisms - somehow this is seen as "playing god" while messing with silicon and copper is not even though these were just as likely or not to have been made by "Her". ;-) Thus commentary on this technology is very pertinent now. Bio-art has been around since the 19th century but did not have the relevance it has now” 11

Bio-art itself has created new ‘dragon’ territory on both the artistic and scientific ‘maps’.

Stuart Bunt describes the difficulties of working in bio-art “We walk a narrow line between beauty and terror, between Frankenstein and wonder. If our artists wish to present a critical view of the science they are often accused of exaggerating the dangers or potentials of a technique. If the work is “beautiful” then we are accused of “promulgating” or making science more acceptable. This is difficult for there is much of beauty to see in nature. Some artists come to us with a view to drawing on nature for imagery yet if the work is too “pretty” we are seen as mere illustrators for scientists.” 12

SymbioticA and the scope of the work being generated by its artists is evidence in itself of the range of practice which is being explored under the umbrella of bio-art and potential debate that is bound to surround this artform. As an isolated and predominantly ‘new’ community Western Australia appears to be an environment which is “not burdened by the past and its traditions of history”13 (Ionat Zurr) which have the potential to limit and constrain.

Immigration, Isolation and the Pacific Rim Perth is a community built on immigration. As non-indigenous settlers we are outsiders struggling to fully understand and survive in this ‘unknown’ land. While not as apparent in the safety of the city and its urban sprawl, with air conditioned cars and buses which carry us in comfort from one safe environment to another, it is this very challenge which divides; it either drives people away or generates a passion for the place and a bond between people and this foreign landscape.

The difference of being an ‘immigrant’ in a new land at the edge of the edge is that “coming from the ‘peripheral’ is significant, because overseas, in major centres artists tend to be inward looking and reference themselves. Perth is more outward looking and open-minded.” (Ionat Zurr) To embrace and support bio-art definitely requires an open mind. However this attitude may also be in the very nature of the person who will move to the edge of the known world from their original home to seek out a new existence. As Ionat also commented, “as an immigrant to another culture you are often speaking cross languages, you are not of the place, you enjoy the experience of being a foreigner and are comfortable with the experience, an adventurer, it is fun a challenge. Everything is new and exciting and you are alert in your observations.” 14

Oron Catts suggests that a “community built on immigration tends to create an amazing collection of misanthropes looking for a difference and independence from the cliques of a traditional cultural context.” 15

While physical isolation is imbedded in Western Australian culture and history, it is no longer such an issue. Air travel and the internet have altered that. Ionat Zurr, (TC&A and Symbiotica artist) suggests that there is a strong focus on new media in Perth “because it provided an escape from the isolation. Artists in Perth have embraced the internet and digital technologies because they gave a means of direct and immediate connection with the world and an escape from the isolation”. 1 Guy Ben-Ary, an artist with Symbiotica comments, “I think that it [the remoteness of Perth] was instrumental in the early days. Before SymbioticA was established. The fact that people here in Uni had time “to spend” on working with artists is something that will not happen in a “big city”. The remoteness of Perth also makes people like Miranda [Grounds] show the beauty and uniqueness of the place and therefore the openness to such ideas. That was what happened with CTEC too …. Some desire to “put Perth on the map” make people hear about it…It is also cheap to live here and it is quite good/easy to develop work here in Perth. I think that SymbioticA could probably not happen in so many other places.” 1 The isolation of Perth is reinforced by strict quarantine regulations that surround the state. Quarantine regulations applied in Australia, and even more rigorously to the borders of Western Australia, is a big issue in relation to bio-art and the exhibition of international works in Perth. The restrictions on the import of living cells has, resulted in artists having to physically come to Perth in order to ‘grow’ their work. In a sense this has worked for rather than against the establishment of Perth as a centre for bio-art. Artists are drawn to Perth in the knowledge that they will have access to world class facilities and internationally acclaimed bio-artists working at SymbioticA. International exchange about bio-art is reinforced through international exhibitions, the presence of visiting artists and residencies at the SymbioticA ‘lab’.

While Perth may seem quite remote it is in fact a part of the Indian Ocean Rim and being a part of the Australian continent we are drawn into Pacific Rim activity and events. Perth is in fact as close by air to some of the countries within this region as it is to the eastern seaboard of Australia. Activity in this region is very accessible and strong connections have been developed between Australia and countries such as Singapore, Indonesia, Japan and more recently China. Many of the opportunities for exchange with the Pacific Rim that exist for Western Australian artists, have been created through the efforts of local individual artists and arts administrators, arts based networks and key national organisations such as Asialink which is based in Melbourne.

Conclusion

It would seem to those living in Perth, that exploration of new territories beyond the known is not unfamiliar at all and may be quite a logical step. Living on the edge of the map of known territories does give rise to new challenges and resourceful solutions. There is not such a great fear of the unknown. Survival is predicated on facing the challenges of a harsh environment in isolation. It is part of our cultural heritage. The physical environment itself presents new and unique challenges for which known solutions are not appropriate. The history, knowledge and solutions from Europe, Asia and America are no longer relevant in this strange land. European cars overheat, fabrics fade in the intense sun, and their buildings store heat in the summer.

While most of those from the edge of the edge live within the relative comfort of the urban sprawl which is Perth we are surrounded by the ocean, bush and the desert. Most of us experience the bush and desert regions at some point in our lives. It is difficult to avoid in fact. The city and urban zone which makes up Perth is in fact an island surrounded and cut off from the rest of the world by sea, bush and desert, literally thousands of kilometres of it.

We are familiar with the isolation and the unusual context.

But maybe this environment cultivates a desire to connect with and be a part of the outside world – to prove ourselves to the world; to not be forgotten and ignored? As Australian comedic character Kath would say in classic colloquial ‘strine’ (ie Australian) vernacular, “look’umoi, look’umoi”. (English translation – “look at me, look at me”).

The extreme landscape and environment of Western Australia impacts on who we are and how we respond to the world around us. The intense light, unique colours and smells bombard the senses with an intensity that cannot be ignored. While there may not be a conscious acknowledgement of the impact that this place has on the emergence of such innovation, it is ubiquitous. It is an ‘environment’ that has created a culture in which initiatives such as SymbioticA, C3 and others have emerged and succeeded internationally. It is a reality that most of us living at the ‘edge of the known world’, are driven by a desire to meet new challenges.

There is no doubt that the creation of SymbioticA has been a key factor in drawing attention to the growth’ of bio-art in Perth. It has created a focal point for both local and international artists with an interest in working with the technology, ideas and issues surrounding this media. It has also profiled the excellent work being carried out by those central to the organisation. Members of SymbioticA are contacted by international institutions to act as consultants and to speak about bio-art.

And why is it so?

We live in land that demands new ways of thinking. There is an exciting sense of collaboration and support that we provide for each other, which may be unique to this community; We are keen to profile the work of colleagues and ensure that our collective achievements are noted on the world map; we are non conformist, outward looking and maybe in some quirky way, we actually embrace and encourage the idea that we live in a land on the map marked “Here Be Dragons”.

Authors

Anne Farren and Andrew Hutchison are academic colleagues in the Department of Design at Curtin University of Technology in Perth, Western Australia. They have been involved in collaborative research into the relationship between technology garment and the body for the past four years. Anne Farren is a Lecturer in Fashion and Course Coordinator, Fashion and Textile Design in the Faulty of BEAD at Curtin University and Andrew Hutchison is a Lecturer in Multimedia.

REFERENCES

1 http://www.maphist.nl/extra/herebedragons.html

2 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/4306936.stm

3 http://beap.org/site/index1.html

4 Bunt, S. 2005 SymbioticA, beauty in the eye of Dr Frankenstein (unpublished article)

5 Bunt, S 2005 Email interview responses 28/11/05

6 Coakley, J 2005 Email 5/12/05

7 http://www.fishandchips.uwa.edu.au/exhibitions/ars.html

8 Zurr, I 2005 Interview with TC&A 2/12/05

9 Catts, O 2005 Interview with TC&A 2/12/05

10 Ben-Ary, G. 2005. Email interview responses 24/11/05

11 Bunt, S 2005 Email interview responses 28/11/05

12 Bunt, S. 2005 SymbioticA, beauty in the eye of Dr Frankenstein (unpublished article)

13 Zurr, I 2005 Interview with TC&A 2/12/05

14 Zurr, I 2005 Interview with TC&A 2/12/05

15 Catts, O 2005 Interview with TC&A 2/12/05

|