| Towards New Bodies and New Biologies: |

Life as Code, Body as ProtocolBy Carlos Castellanos

Introduction: In Search of the New Body ...the world appears to us as an endless and unstructured collection of images, texts, and other data records, it is only appropriate that we will be moved to model it as a database. But it is also appropriate that we would want to develop a poetics, aesthetics, and ethics of this database." 3 Thus, the database becomes more than just a neutral technical tool. It has the potential to organize and standardize culture according its own internal operating logic. It becomes a potent force, influencing how a society perceives and defines itself, perhaps to the point where there is no cultural view apart from that which the database, and technology in general, bring forth. In the world of biotechnology, database logic can shape the boundaries between the informational and the biological, between technology and the body. New media, and computing in general also give us the notion of protocol, which in an increasingly networked world, becomes more important to understand, for it can shape the aforementioned boundaries and dramatically affect the organization of culture in new and profound ways. In computing, a protocol refers to an agreed upon standard or set of rules that enable connection, communication and data transfer in computer networks. The concept of protocol is at the core of network computing. In the network of networks, the Internet we have TCP, UDP, FTP and HTTP (the protocol behind the web), which are but a few of the protocols that govern the flow of data across it.4 For computers to be able to communicate over the Internet they must implement an entire set of protocols. These protocols, when taken together form what is known as a protocol “stack”, more formally referred to as the 7-layer OSI Model5. The implementation of these protocols are what allow communication to happen on the net. Most of these protocols are invisible to the general user. They usually only encounter those on the top or “Application layer”. Programs such as web browsers and e-mail clients function on this top layer. Underneath however, are countless other protocols that rigidly structure how data is to move across the net. Contrary to its popular notions as an open, chaotic, frontier without rules or structure, the Internet is entirely constituted of protocols. In fact it is not inaccurate to say that Internet protocols and the Internet are in fact one in the same. Without them the net would simply not exist. Thus it makes the net all about rules, structure and control. Further to the point it, it is becoming apparent that protocol does not merely function technically, or only in computer networks. Much like the tendency to organize seemingly disparate media into a database, there is also a trend toward the structuring of society's political and social entities into that of a networked and protocological control model. Alexander Galloway and Eugene Thacker suggest that the techniques, conventions and implementations of protocol function simultaneously on both a technical and political level. They see protocol as a “totalizing control apparatus”, affecting both the technical and political formation of computer networks, biological systems, and other media: ...protocols are all the conventional rules and standards that govern relationships within networks. Quite often these relationships come in the form of communication between two or more computers, but “relationships within networks” can also refer to purely biological processes, as in the systemic phenomenon of gene expression. Thus, by “networks” we want to refer to any system of interrelationality, whether biological or informatic, organic or inorganic, technical or natural... 6 Thus as these new “systems of interrelationality” expand their influence and importance, power and control structures are being transformed, new institutions are emerging and old ones are being reorganized. Protocol distinguishes itself from previous forms of power and control (hierarchies, bureaucracies, etc.) not only in its very form (decentralized, distributed) but also in its goals and behaviors. Galloway and Thacker highlight some of these qualities: • protocol facilitates relationships between interconnected, but autonomous, entities; • protocol’s virtues include robustness, contingency, interoperability, flexibility, and heterogeneity; • a goal of protocol is to accommodate everything, no matter what source or destination, no matter what originary definition or identity; • while protocol is universal, it is always achieved through negotiation (meaning that in the future protocol can and will be different); • protocol is a system for maintaining organization and control in networks.7 Thus protocol is fluid and flexible, expansive and autonomous. And it has the potential to reorganize the social, political and cultural landscape according to this dynamic. Much as the conoidal bullet fundamentally changed the methods and strategies of warfare8, the distributed nature of all networks, but particularly computer networks and (in the biotech century) biological networks, are fostering new organizational models of institutional power and control, namely distributed and autonomous control.9 Because of their very nature, the occurrences and enactions of these new models are difficult to locate or even describe. There is no one network of control but multitudes of autonomous yet connected self-organizing nodes that can enact their will and profoundly affect relations both within and between varied institutions, industries (military, science, media, etc) and individuals. This amounts to a new emergent framework of political and cultural organization.

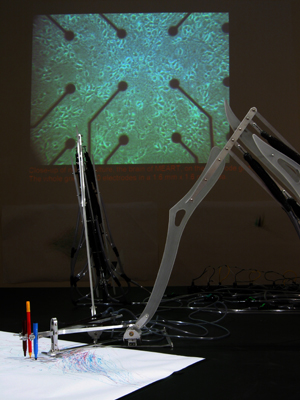

Setting aside its role in the aesthetics of information, Carnivore, as contextualized by Galloway, can be seen as a form of conceptual art. Much like the work of artists such as John Cage and Sol Lewitt, Carnivore is a set of instructions that can be implemented at a later time. Of course this can be said of all software art (indeed of all software). What sets Carnivore apart is that it serves to reveal and take on issues of protocol head on. It takes a law enforcement tool and makes it available to all, especially artists. It can serve to reveal how power and control functions in the decentralized world of protocol, and how they can be subverted. It is undeniably a creature of protocol. It is protocol in action. Biological Bodies The world of biotechnology is predicated on the idea of genetic “information” and the understanding life as “code”. This merging of the two traditionally separate domains of molecular biology and computer science (each with very different views on the body) highlights a unique characteristic of biotechnology which differentiates it from computer and information technologies. As Eugene Thacker states: Instead of being focused on disembodiment and virtuality, biotech research's approach to informatics is toward the capacities of information to materialize bodies (bodies amenable to current paradigms of medicine and health care).11 So while computer and information technologies tend to efface the body, biotech engages it, seeking to redefine the body by materially reconfiguring it through information - and as Thacker contends, to control it as well. Which brings us back to the discussion of protocol. May we speak of protocols in biological networks, just as we do in reference to computer networks? With a similar influence on power relations? Galloway and Thacker contend that protocols exist in one just as they do in the other: While molecular biology, genetics, and fields in biotechnology do not use the technical term protocol, they nevertheless employ protocols at several levels... We can begin by suggesting that the protocols of biological networks are the modes of biological regulation and control in the genome and in the cell. ...molecular interactions (DNA complementarity, enzymatic catalysis, molecular binding) are understood to construct networked relationships, such as the transcription of DNA into RNA, the conversion of sugar molecules into usable energy, or the infection by a viral or bacterial agent....”12 Thus, as the biological and the informational become part of the same “totalizing control apparatus”, sharing their “systems of interrelationality”, the potential for new forms of power and control have to be considered when we speak of the biotech, just as they are considered when we speak of infotech: Protocol answers the complicated question of how control pervades distributed networks. In other words, protocol tells us that heterogeneous, asymmetrical power relations are the absolute essence of the Internet-network or the genome-network, not their fetters.13 As the ultimate target of most biotech research, the body currently occupies the turbulent boundary zone between the biological and the informatic. Thus, it becomes in a sense subsumed by the world of protocol, which brings up a multitude of questions about its place in culture. How is it affected as it is increasingly networked through information technologies and thus becomes more and more integrated with the world of protocol? Is the body itself emerging as a protocol? Or a protocological agent? Will the traditional distinctions and boundaries of the body still be useful in the future? SymbioticA is a research laboratory in western Australia that focuses on research and artistic exploration in biological technologies. It is an artist-run laboratory where artists “actively use the tools and technologies of science, not just to comment about them, but also to explore their possibilities.”14 It allows them to work free of the often rigid demands and constraints common in mainstream scientific research. SymbioticA is primarily a “wet lab”, focusing primarily on tissue culture-based art works. Their Tissue Culture and Art Project includes such works as Victimless Leather and Disembodied Cuisine, where semi-living tissue is grown into leather jackets and food respectively. Perhaps the project most relevant to the discussion here, as it most clearly demonstrates the merger of silicon and flesh, is Fish & Chips. This project features fish neurons grown over silicon chips, which are connected to hardware and software that generate sound and visuals. It renders the idea of “programmable flesh” into reality. Their web site explains the rationale behind the project: Biology is evolving from a phase of discovery into a phase of creativity and utilization. The effects on society will be profound... The cybernetic notion of interfacing neurons with machines/robots is starting to become a reality. By creating a temporal "artist" that will perform art-producing activities "Fish & Chips" explores questions concerning art and creativity... How are we going to interact with such cybernetic entities considering the fact that their emergent behavior may be creative and unpredictable?15 It is certainly a short leap of logic to look at this project and envision a world of programmable human flesh. But what does programmable flesh really mean? As Katherine Hayles has noted, the idea of the cyborg relies upon the concept of information as something separate from the material forms that give rise to it.16 Information is disembodied at its core. Intelligence is equated with the formal creation and manipulation of symbols and information patterns. These information patterns, it is believed, can pass unaltered from one material substrate to another. This is what is at the heart of most computer science research, and it acts as a potent force to continually efface the body and eliminate embodiment from digital technologies. As previously mentioned, biotech does not efface the body but seeks to materially alter or enhance it. Yet biotech research, much like computer science research, also believes that information can pass unaltered from one material substrate to another. Indeed, in the world of biotechnology the body expresses itself through information (in the form of DNA code, genome databases, protein sequences, etc.). How then would one interpret the workings of Fish & Chips, where information patterns are not abstract and disembodied but a material property of a hybrid techno-biological entity? Perhaps not (yet) intelligent but exhibiting signs of autonomy and self-organization, even at such a nascent state of development. Here, the information pathways sit uneasily between “wet” and “dry”. Not quite cyborg, since the silicon is not injected or fused with flesh but organically grown with it, rendering this entity's information generation and transmission as a property of its biology. What happens to this information then? Would it still be the same information if it were to be “uploaded” to a web server or personal computer – or human cells? Would any piece of information passing through something like this remain unchanged? Our cultural conditioning would lead us to say yes. In fact, Claude Shannon's Theory of Information formalizes this thinking, defining information as an entity distinct form the medium that carries it, with only the “noise” on the line serving to corrupt it.17 This thinking is at the heart of biotech research, where information is routinely passed between wet and dry. But intuition and reasoning may lead one to think otherwise. What then, do we make of Fish & Chips? Is it an “embodied” computer? Is it the digital word made flesh? The flesh made digital? Ultimately, Fish & Chips serves to highlight biotech's potential to enhance the biological and redefine the body (or at least the flesh) in its own image. Still biological, yet somehow something more. Like Carnivore, it is a material occurrence of the “totalizing control apparatus”, only this time it is biological protocols that are subverted for artistic ends. But Fish & Chips also demonstrates how the biological can serve to inform the world of the informational, to give information the body that it lost. In all of their work, SymbioticA confront us with actual physical glimpses of potential futures being made possible by biotechnology. They force us to ask ourselves if we are ready to deal with the consequences of our skills and knowledge in the life sciences. Their work is often provocative and controversial, some may even consider it audacious. In this sense, it is firmly seated in the artistic tradition of risk-taking and iconoclasm. It shows us things we would not otherwise see and asks uneasy questions that would not otherwise get asked. The Determined Body Speaking on her ideas regarding the development of a “technology of embodiment”, artist/researcher Thecla Schiphorst calls for an inversion of prevailing cultural views regarding the body's relationship with technology: When we view body intelligence as a subcategory of technological production, the experience and knowledge of the body becomes determined, informed and molded by the Technological Ethos. What would happen if we inverted this viewpoint? Could it be possible that these same technological processes can be seen as subcategories of physical experience and consciousness, informed and transformed by kinesthesia, embodiment, and physical memory?18 To put it another way, our knowledge of our own bodies seems to be shaped by the organizing and standardizing logic of Manovich's database and Galloway and Thacker's protocols. Schiphorst believes that our technologically determined culture (which values materiality over physicality) privileges its own definition of the technical, and thus has all but eliminated physical experience from its vocabulary. To reverse this trend, or at least make people aware of it, Schiphorst seeks to develop interactive art works that make participants conscious of their own physical processes and to have computer systems informed and influenced by these processes. Stemming from her background in both computer science and dance, much of Schiphorst's work, particularly The Whisper[s] Project, involves a desire to discover and map “data patterns” of the body.19 This is similar to what Eugene Thacker calls the identification of “patterns of relationships” that can be gleaned when moving between DNA “code” and computer code.20 But she also tries to bring an intimate and sensual aesthetic to her projects, something she feels is missing from digital media works. Although not necessarily a “bio-artist”, Schiphorst's work still shares some important similarities. First, she often works off the premise that the body can be expressed through information (“data patterns” of the body). Like biotech, her work seeks to use the world of the biological to inform the world of the informational. Her work shows us how the body can indeed emerge as a protocological agent. Potentially helping to determine technological directions, rather than being determined by them. New Bodies and New Biologies Certainly the analyses and artists presented here are intended as nothing more than a starting point for further discourse. Indeed, there may be more questions now than when this essay began. And perhaps that is the goal. The cultural and political realignments emerging from the collision of the protocological and biological arenas means that some deeply held concepts relating to life, biology and our bodies need to be reexamined. As the monitoring, regulation and production of bodies, and indeed life itself begins to function in a networked, protocological paradigm, the old familiar boundaries start to dissolve. Are we ready for this shift? How will we manage both the dangers and opportunities brought about by the joining of the protocological and biological? Will we recognize ourselves in the future? The perspective that can be brought to these questions by artists and other “non-experts” from the humanities may prove useful if we are to move forward with our eyes wide open. Notes 1 Taken from Jeremy Rifkin's The Biotech Century: harnessing the gene and remaking the world (New York: Tarcher/Putnam, 1998). 2 While not directly referencing them, my notions of power and control (and those of many of the authors cited in this article) are, at least indirectly, drawing on the writings of theorists such Gilles Deleuze and Michael Foucault, among others. A lengthy discussion into their ideas is beyond the scope of this article, but for a quick sample that may provide some insight into how I am referring to these terms see Gilles Deleuze, "Postscript on the Societies of Control", from October 59, Winter 1992, pp. 3-7. 3 Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2001). 4 For a more thorough technical understanding of protocols see Eric A. Hall, Internet Core Protocols (Cambridge, Mass: O'Reilly, 2000). 5 For a detailed explanation of the OSI Model, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OSI_model. 6 Alexander Galloway and Eugene Thacker, “Protocol, Control and Networks”, Grey Room 17, Fall 2004, p. 8. 7 Galloway and Thacker, “Protocol, Control and Networks”, p. 9. 8 See Manuel DeLanda, War in the Age of Intelligent Machines (New York: Zone Books, 1991). 9 For more on how power and control are changing due to the influence of protocols and the Internet see Alexander Galloway, Protocol: How Control Exists After Decentralization (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2004). 10 Radical Software Group (RSG). http://itserve.cc.ed.nyu.edu/RSG For more information on Carnivore see http://rhizome.org/carnivore 11 Eugene Thacker, “Data Made Flesh: Biotechnology and the Discourse of the Posthuman”, Cultural Critique 53 (Winter 2003), pp 72-97. 12 Galloway, Thacker; “Protocol, Control and Networks”, p. 16. 13 Galloway, Thacker; “Protocol, Control and Networks”, p. 20. 14 See http://www.symbiotica.uwa.edu.au/info/info.html 15 See http://www.symbiotica.uwa.edu.au/research/fishnchips.html 16 Katherine Hayles notes that the currently prevailing cultural belief is that information can move across different material substrates and still remain unchanged. She claims that there is a presumption of information as a “disembodied entity that can flow between carbon-based organic components and silicon-based electronic components to make protein and silicon operate as a single system.” See N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), pp 1-2. 17 C. E. Shannon, “A mathematical theory of communication,'' Bell System Technical Journal, vol. 27, pp. 379-423 and 623-656, July and October, 1948. 18 Thecla Schiphorst, Body Noise: Subtexts of Computers and Dance. http://www.art.net/~dtz/schipo3.html 19 See http://whisper.surrey.sfu.ca/ 20 See Eugene Thacker Biomedia (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2004). |

|||||