Issue 28 11.20.13

Biohacking

by Sara Gevurtz

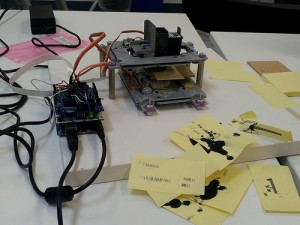

Recently there has been a growing trend of do-it-yourself spaces popping up. These spaces allow anyone who is just curious or crafty to create and build new things. A recent space that focuses on “biohacking,” or experimenting with biology, has opened in the Silicon Valley. I have recently checked out this new hackerspace, Biocurious. Biohacking is gaining momentum and is now making its first appearance in the Silicon Valley; it is a movement being led by scientists, artists, and cultural critics who are attempting to create public awareness and access to biological information. A biohacker is someone who is, essentially, doing biology as a hobby, not for a career. It is very similar to the idea of someone who hacks computers as a hobby. This all fits into the recent do-it-yourself (DIY) movement that has developed and is the main reason for the biohacking phenomena. The DIY movement includes people starting to grow their own food, make their own clothes, and backwards-engineer computers.

I discovered Biocurious as a meetup group. This group is a little different than your run-of-the-mill social group. The people developing the group have spent copious amounts of time and energy creating a “hackerspace” that is open for experimentation by the Biocurious community. In September 2011, the group officially opened their doors and started their first community workshops.

Since I have a background in biology and create art that is concerned with science, I felt that it was necessary for me to attend these first workshops. As one might expect, with a DIY culture, I found a group of highly motivated and curious people. The founding members of Biocurious are passionate about what they do, and yet not all the members came from the biology field.

The first workshop I attended was about biospheres, which are self-contained ecosystems, and how to make them. We did the simple process of making our own personal biospheres in jars and learned about the greater implications of biospheres, from the history of experimentation revolving around them, to their commercial aspects.

The second workshop involved lab work and how to properly culture glowing bacteria. Now, anyone who is remotely familiar with science realizes that inserting genetic information from one species to a foreign species is the bread and butter of genetic engineering. The process was fairly simple, and anyone with high school lab knowledge would be able to do it. Getting bacteria to glow requires inserting the green fluorescent protein, or GFP, from jellyfish into the bacteria. Bacteria have a circular DNA, called a plasmid, which make it very easy to insert foreign DNA without disrupting the cell’s primary functions, which are on the bacteria’s main separate DNA strand. My knowledge of pipettes slowly came back to me—science is just like following a recipe.

If we look at early bioart, Eduardo Kac in 2000 created a “GFP Bunny,” named Alba that was a green fluorescent rabbit. In another piece Genesis, Kac created a gene that was a translation of a sentence from the book of genesis and had it inserted into bacteria that was then cultured.

Many of these projects required collaborations between the artist and a scientist. It is often difficult to find a scientist who is willing to help an artist navigate the laboratory to complete the sorts of projects Biocurious engenders. However, with the combiniation of DIY bio and hackerspaces with people who do science for fun, hackerspaces like Biocurious make future artist and scientist collaborations possible. If nothing else, these places allow artists to access equipment and a community that is interested in biology.