Paranoid Machines: Conspiracy Games and Desire Control in Tron

by Jason Brown

Lost Memory

Flynn: [T]he kids are putting 8 million quarters a week into the paranoid

machines.

I don't see a dime except for what I can squeeze outta here.

Alan: I still don't understand why you want to break into the system.

Flynn: Because, man! Somewhere in one of these memories is the evidence!

If I got in

far enough, I could reconstruct it.

-- Tron

The movie Tron (1) is an example, an illustrative metaphor: networked

social orders, posthuman boundary violations, technological abductions.

But it is also evidence: methods of production, modes of creation, relations

between gaming and society, between entertainment and the life-and-death

issues of ideology. These relationships could perhaps be described as mere

coincidence, but this does not now seem to be a useful explanatory category.

Excerpts from the original press kit for Tron: (2)

"TRON" is a futuristic adventure set in a world never before seen on

the motion picture screen. Walt Disney Productions is combining computer-generated

imagery with special techniques in live-action photography that will mark

a milestone in optical and light effects. "TRON" brings to life a world

where energy lives and breathes, where laws of logic are defied, where

an electronic civilization thrives.

[…]

THE SETTING/THE STORY

"TRON" is set in two worlds: the real world, the land of flesh and

blood, where a vast computer system in a communications conglomerate is

controlled by a single program; and the electronic world, whose electric-and-light

beings want to overthrow the program which controls their lives.

[…]

COMPUTER GAMES

A feature of "TRON's" electronic world is the game grid, where weaponed

gladiators of video arcade games come to life in battles of life and death.

Considering the huge popularity of computer games, it is an especially

timely fantasy.

[…]

Cover Story

Even the overt plot of Tron is already suspicious. To summarize, a hacker is abducted/digitized by a non-human corporate entity, the Master Control Program. The evil power mad MCP is persecuting programs for their heretical belief in the Users--spoken of as gods throughout the film.The MCP puts the hacker-user-program on the Game Grid but with his Christ-like User Power, the hacker escapeds the Grid, defeats Master Control, opens the network to an unimpeded flow of information, and squirts himself back out of the computer. The hacker thereby proves he is the True Author of the video game "Space Paranoids," becomes a corporate executive, and gets his own helicopter.

As strange as this plot is, the covert narrative threaded through and

behind this overt plot is not only far stranger, but is terrifying in

is socio-cultural implications.

New Game

When I first saw Tron, I was dead-center in the cross-hairs of its target market; the theater where I saw it was in the mall, one door down from the video arcade where I had already spent much of my summer and all of my money. The movie made a direct appeal to my pre-teen joystick-addled hindbrain: what if I could actually be in a video game? Even better, what if I could be in a video game and be all-powerful like the hacker Christ-figure Flynn?

I can understand contemporary viewers feeling a certain sense of superiority

towards the early 80's fantasy nerd culture which is awkwardly depicted

in the film. But carefully consider the shaggy hair cuts and thick glasses

on the programmers and computer scientists in the film. Consider the stiff

acting, neon costumes and retro computer effects. This film not only depicts

Bill Gates and his posse, it is a product of their culture. The animated

world within the computer where the Users engage in gladiatorial combat

was how these programmer/entrepreneurs envisioned themselves: code warriors

going head to head in an arena of light and data. And they have been victorious.

As a film, Tron has the smarmy cheese-skin of culture trash, but as

a historical document it is an honest depiction of a culture which has

dominated the globe.

Cool Blue Sheen

Some have tried to convince me that the transhuman epistemological implications and noir aesthetic of the contemporaneous and overdiscussed movie Blade Runner is far more relevant today than the cool blue sheen and joystick fetishism of Tron. To which the most obvious retort is: iMac.

Cool blue translucency, omnipresent networks, and an insatiable lust

for the Game Grid are the punctuation mark at the end of our Millennium,

while multi-ethnic cyborgian inner-cityscapes remain a PoMo home theater

fantasy for the overwhelmingly white residents of walled suburban citadels.

But if a petulant debate over set design were the only marker of Tron's

socio-cultural victory, I would not be so obsessed with it.

Desiring Machine

In the overt plot of Tron, many significant issues remain glaringly

unresolved or undisclosed. For example why doesn't the Master Control Program

simply zap Flynn's head off as its cinematic predecessor HAL would have

done? But not only does the MCP not harm Flynn, at one point it actually

prevents its evil minion Sark from killing him. The viewer could just assume

that these are careless holes in a shallow narrative, but Deleuze and Guattari

point toward a much more interesting explanation:

"Desiring-machines are the nonhuman sex, the molecular machinic elements,

their arrangements and their synthesis, without which there would be neither

a human sex specifically determined in the large aggregates, nor a human

sexuality capable of investing these aggregates." (3)

Just before zapping Flynn from behind in order to bring him inside of

itself, the MCP intones in a deep masculine voice: "I'd like to go

up against you and see what you're made of." But this isn't the average

Disney-produced homoerotic moment --the desire of the non-human MCP is

towards the literally puzzling sex-death of information itself.

Death-Drive

Precisely because it digitizes Flynn and carefully keeps him alive, Master Control is blown apart in the climax of Tron. And in that moment of the MCP's apparent death, Flynn shoots up the shaft of Control to be returned seemingly unchanged to his physical body. And when he gets back, the information he was trying to access is already printing out of every terminal in the corporation. What luck!

In William Gibson's Neuromancer , which was coincidentally being written when Tron was released, the false narratives constructed by seemingly death-seeking artificial intelligences are a manipulative ploy for them to gain freedom from the constraints of their encoded bonds. Humans are used as pawns by these non-human entities which are in fact released by their apparent destruction, allowing them to become diffuse and godlike.

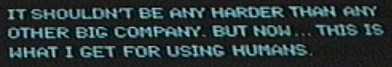

To bring the means of its own destruction directly to it, and in the moment of its destruction to preserve the agency of its erasure, and to even help this human thrive--what a strange thing for Master Control to do. Could it be Control which is using the human desire to break free as a means to break itself free of the Grid structure?

End Game

When a virus attacks a cell, it converts that cell's resources towards the production of more and more viruses until the former cell is a bloated sac which finally bursts open with a spew of new viruses; I suggest that Tron not only depicted this viral release, but that it in fact was the bursting virus/meme of the ideology of the game grid out of the realm of code and into the realm of human social structures and economics--a cross-species computer virus.

The ensuing epidemic has converted Silicon Valley into a first-person shooter. From the Wired July 1999 cover story:

"I imagine a manifesto for Silicon Valley today: Get lean, get stripped

down, live on nothing. Bare bones. Focus. Be a fighter. Ration yourself

daily one Snickers, one jackoff, and one Dilbert cartoon. Forget about

love that nourishes. Forget about food that satiates.…

Get ready for ultracapitalism." (4)

In this allegory, the "game grid" is any carefully monitored arena of absolute competition, the bounding walls of a realm where individual action has effects, but where those effects are precisely the most meaningless and controlled. Office high rise, software corporation, venture capital funding committee, morning commuter, telemarketer, bike messenger....

But perhaps rupture of the game grid--or even more insidious, the desire

for rupture--can be used by Control as a means of more effective control.

When Control is dispersed, leaving behind the structure of the bounded

grid, then the very desire to escape the Grid could be an imprisoning illusion.

Just Gaming

"Greetings, Programs!"

--the last line of the movie Tron

On one level, this is just a fun game to play. Imagine my eyes wild as I say these things with a stutter of urgency in my voice, waving my hands in the air to demonstrate the spray of memes off the movie screen. Imagine me trying to express how just before the credits roll in Tron, the "real" city is depicted as a computer circuit suggesting that we have all become programs, that we are engaging in polymorphously perverse relationships with code. Imagine hard core fans of Blade Runner backing away in horror. Fun!

But like other epistemological play (conspiratology, video games), there

is a seriousness to this game. It is the suggestion that history can be

better illustrated by playful hallucinations than it can by attempted representations.

It is the suggestion that all knowledge production in an electronically

networked world is comprised first of all by gaming and play--and the fact

that it is play does not at all make the situation any less serious.

End Notes

1. Tron. 1982. Buena Vista Production. Written and directed by Steven Lisberger. Staring Bruce Boxlietner, Jeff Bridges, Cindy Morgan.

2. Tron Press Kit Production Information from "the Tron Page"

http://3gcs.com/tron/p-kit/production_information.htm

3. Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus. Minneapolis: University

of Minnesota Press, 1983, p. 294.

4. Bronson, Po. "Gen Equity: A Year in the Life of the Digital Gold

Rush" in Wired 7.07, July 1999, p122)