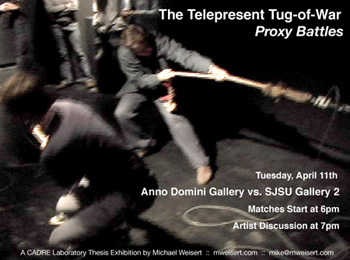

| The Telepresent Tug of War |

|

By Michael Weisert

Below is an excerpt from my research documentation of the project. I discuss the cultural history of the tug of war, from its origins in China and Japan, to the more recent competitions held in Okinawa and San Francisco. It also examines competitions of pride, especially the duel. The final segment discusses the cultural significance of sport, especially within American society, to answer questions about its influence on art. "The Telepresent Tug of War" will be shown again at ISEA2006/Zero-One San Jose this summer at Works Gallery in San Jose.

Competition of Pride: The duel, the tug of war and John Henry

“In America one only fights to kill; one fights

because one sees no hope of getting one’s adversary condemned to

death. There are very few duels, but they almost always end

fatally.” Alexis de Tocqueville, 1831 (Baldick pg.115)

In the (American) West, especially California, the duel was a primary means of conflict resolution and entertainment. In the 1850’s, San Francisco became known as the dueling capital of the U.S. Local papers would advertise duels as street and stage performances for local residents to attend. It is arguable that these duels of honor were the first performance artists in California (apart from the original, displaced natives). One duel in particular utilized a primitive form of news updates to create a comparison between the two participants. In San Francisco, Southerner Colonel William Gwin and J.W. McCorkle decided to settle their dispute via a duel with pistols. Colonel Gwin’s wife refused to attend the match in fear of watching her husband die. To give her up to date progress of the duel, a messenger ran back and forth between the duel and her home located a few blocks away. After each shot, she received notification that the attacker had missed his target. Oddly enough, both men failed to hit each other after many volleys of bullets and the duel was considered a draw. Mrs. Gwin was saddened by the poor display of accuracy by both men. (Baldick) This story relates to the Telepresent Tug of War in that the messenger in this story is acting in the same manner as the TCP/IP line in the artwork. He is delivering packets of information to Mrs. Gwin, who is able to assess the situation from a distance. In the TToW, two monitors located next to each unit stream the comparative data to observers on the contest.

San Francisco was the scene of an altogether different display of dueling in 1894. Billed as “the greatest international tug-of-war tournament ever held in this or any other country”, the tournament hosted teams from eight different countries (U.S., Canada, Scotland, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Denmark, and Russia.) To measure the distance pulled by a particular side, the judge was raised above the ring and slid a ball down a rail to measure the distance the rope had traveled. This method was an excellent analog solution to the problem of force measurement (The TToW utilizes devices known as “load cells” to solve the same issue, which will be covered in the final section of this document.) More than 10,000 people filled the pavilion to watch Canada leave with victory. The popularity of the event led to the adoption of the tug-of-war into the Olympics in 1900. It was finally dropped from competition in 1920.

Although the San Francisco tug-of-war was successful in drawing alarge crowd, it pales in comparison to the number of people who participate in the Naha tug-of-war held annually in Okinawa. An estimated 25,000 people participate in a tug-of-war using a rope weighing 40 tons and is 100 meters long. The contest lasts for thirty minutes and begins when team leaders stand on top of the rope and command their teams into place. Teams are separated between East and West, which is symbolic of the two ruling dynasties of Naha from centuries ago. “The tug-of-war dates back to 1600, when it served a duel purpose. Villagers from east and west did honorific battle for victory as a sign to shamans who predicted the future. The prayers were for a good rice harvest. The second motive was to instill peace and stability into the lives of seafarers of this island nation, and to insure their safety.” (Japan Update.com)

The story of John Henry is a tale about a man who overcomes a machine in an industrial race. In the process, he dies from exhaustion immediately after defeating his mechanical foe. I want to briefly touch upon John Henry to bring to discuss the American tale of man vs. machine. In American culture we see an abundance of reoccurring stories in which the machine is an enemy to be feared. These stretch from the tale of John Henry, to movies such as Metropolis and The Matrix. The story of John Henry offers a possible explanation for this fear. During the industrialization of America, many people were displaced from their traditional job roles. The machine had effectively destroyed the jobs of much of rural America. This destruction was illustrated in the novels The Grapes of Wrath as well as Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. By overcoming a machine, a cause of the Great Depression turmoil, makes John Henry the hero. When using the Telepresent Tug of War, users are physically struggling with a machine that is loud and powerful. With the users in different locations, all a participant can experience is this battle with a winch. At what point does the user separate the physical experience with the mechanical and the data driven from another human participant? The acceptance of the device as a bridge between two players relates directly to the nature of sports in general.

Sport as Cultural Icon: Baseball, Boxing and Soccer

Beyond the tragic character, art and sport also share a rich history within religion in western culture. Art, especially through the Renaissance, was closely tied to Catholic theology in its subject matter. Ancient Greece and Rome used sport as public performance as well as a cultural system to build class hierarchy. It is this tie to ancient Rome, namely paganism that led early Catholics to demonize sport. This belief still carries on today in American society in which it is a societal belief that athletes sacrifice intellect for physical prowess. (sport pg. 91) Eastern culture holds an exact opposite view of sports. The focus on harnessing life force through body to promote spiritual growth is central to most eastern religions. I am most interested by the embodiment of a theology into athletics and art. When countries meet in the Olympics it becomes small battles of theology enacted through game. Great examples include: the 1933 games in Berlin, in which the United States faced off with Hitler’s “supermen”, the 1973 games in which the Russians defeated the United States in Basketball, and the 1980 games in which the U.S. Hockey team defeated Russia. In art, cultural battles have taken place in the early 1900’s when the United States worked desperately to shift the cultural focus from Paris to New York, or the more recent push of Asian / Pacific Rim culture to overcome an Atlantic-based art world. By focusing attention on a particular location, participants justify their beliefs and build a sense of national pride. This rule applies both sport and art. I began this section by singling out three sports: baseball, boxing and soccer. I selected these each one represents society at a national, regional and individuel level. Baseball is mostly considered an American sport, although which America (North or Central) I am referring to is debatable. The recent World Baseball Classic has brought this title into question. Baseball dissects America into regional rivalries in which similar regional locations battle for ideological superiority. The most obvious of these are: San Francisco vs. Los Angeles, Oakland vs. Anaheim, Cleveland vs. Chicago, and New York vs. Boston. Soccer, as opposed to baseball, is played widely on a national stage. During the first exhibition of the TToW, it was widely suggested that a Telepresent game was an excellent alternative to warfare. This argument is debatable when we consider the World Cup “Soccer War”. In 1969, El Salvador invaded Honduras after three hotly contested matches. Soccer has also been responsible for diplomatic strains between several African countries. In the beginning of the Iraq war, we learned the plight of the Iraqi soccer team. After their previous defeats, they were subject to torture by the Hussein family. On an individuel level, boxing has played the metaphor for the common man in both English and American society. America has rallied behind boxers such as Mohammed Ali, Sonny Liston, and James Braddock (as depicted in the recent film, Cinderella Man.) The boxer is easily compared to the “champion” of the duel as I previously discussed. The modern day boxer is an ideological champion for the common man. One lesser-known boxer, Tom Molineaux (a slave in 1810), was granted his freedom when his owner was in awe of his abilities. Tom went on to represent the United States in a fight versus Great Britain’s Tom Cribb. Molineaux was able to overcome racism due to his physical abilities in a sport central to American ideology. Throughout the history of art, different movements in art have made it central to their ideals to embody the values of their specific region. In American art, these movements included the Ash Can School, the American Landscape Painters and Regionalism, while all modernist art movements have specifically been created to promote a set a set of values.

Baldick, Robert, “The Duel: A History of Dueling” Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. New York, New York. 1965 212 pgs. |

|||||||||||

In the second week of April in 2006 I held a competition billed as "The

Telepresent Tug of War". This event featured two large steel

cages each containing a two-ton winch. Linking the devices across

eight blocks of downtown San Jose was a bit of Python code comparing

strength data about the participants. The game worked in a

similar fashion to a traditional tug-of-war. You pull the rope, I

move forward. From this competition I found emergent pockets of

team pride, a bit of show-boating and alot of enthusiasm to be a part

of the game.

In the second week of April in 2006 I held a competition billed as "The

Telepresent Tug of War". This event featured two large steel

cages each containing a two-ton winch. Linking the devices across

eight blocks of downtown San Jose was a bit of Python code comparing

strength data about the participants. The game worked in a

similar fashion to a traditional tug-of-war. You pull the rope, I

move forward. From this competition I found emergent pockets of

team pride, a bit of show-boating and alot of enthusiasm to be a part

of the game.